I am terrible at learning languages. There are people who can grind a new language for six months and come out the other side never needing to switch to English when speaking with a native. They speak three languages fluently and can get by in three more.

Then there are people like me. People who took three years of Spanish in high school, two years of Spanish in college, and grew up with Mexican soccer games on TV on at friends’ houses, but who couldn’t order a taco in Spanish at the end. Then I tried to learn Hebrew, and I couldn’t even recite the alphabet to you now.

And, yet… here I am. I’m a native English speaker and I attend a Francophone church, I navigate my kids’ Francophone schools, and I’ve even argued (and won!) an appeal in front of the Tribunal de Justice. Soon, if all of my paperwork goes well, I’ll even be French.

I want to talk about how I got this level of fluency, even as someone who is terrible at language learning.

(Sorry, there’s no secret in what I’m about to share. The answer is what you don’t want to hear. It’s time and hard work. But read on anyway, it might be interesting.)

If you’re not good at learning languages, the best tool you have is time. Calendar time–how long you’re willing to stick with the language–and invested time.

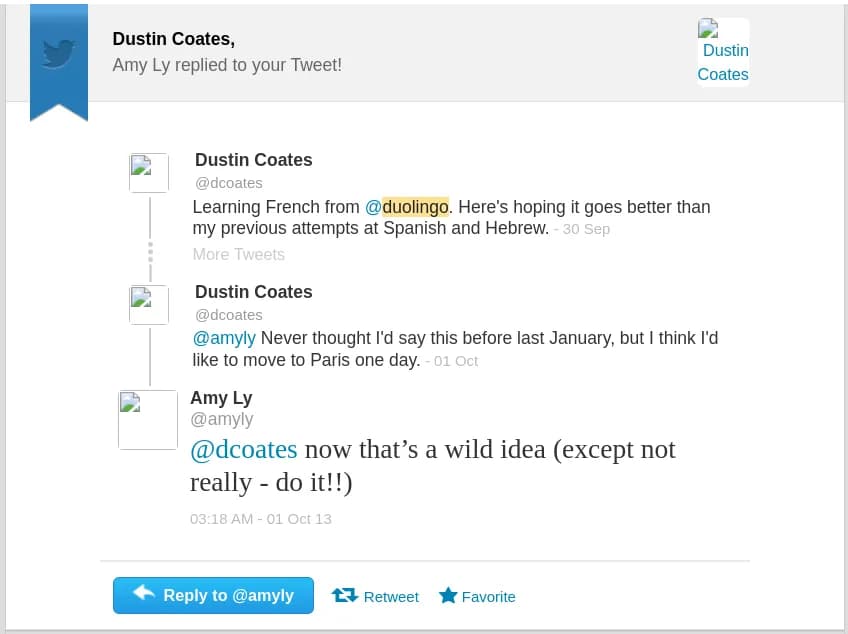

I started learning French in the fall of 2013, so just over ten years ago. It wasn’t an amazing start. I downloaded Duolingo and tried a few lessons. Now, a lot of people who are very serious about learning languages will tell you that Duolingo isn’t a great way to learn a language. And, you know, it probably isn’t. But what those people miss is that the greatest resource is one that will keep you involved. Duolingo does a great job at that. The gamification gives new learners an immediate reason to keep coming back when their greater reason, such as reading L’Étranger in the original French, seems unattainable.

The serious language learners don’t need that push, as their motivation is language learning itself. Which is great! However, they must realize they are decidedly abnormal in this aspect.

Of course, ten minutes of an app a day isn’t going to make anyone fluent. That’s where the time you’re willing to invest comes in.

Now, you’re going to want to trick yourself into thinking that there are certain learning resources that will get you to fluent faster and that you can figure out what they are. There are certain resources that are better than others, but the time you waste trying to figure out the optimal resource mix is probably more than the time that the optimal mix will save you. Go online, find a few recommendations in a forum, and choose the one that seems more “right” to you.

Also don’t give in to the feeling that buying or downloading a resource equals learning. It’s attractive, because your mind senses that you’re doing something, and it gives you the feeling of progress. It’s easy “progress,” too, as all you had to do was put down some money. It isn’t progress, though. Only hard work will give you that.

The faster you want to be fluent, the more time per day you have to invest in it. This is easy in the beginning. While you still have difficulty in forming or understanding sentences, every day you are visibly understanding more than you did the day before. Learning even gets a bit more enjoyable as you go as you’re able to make more connections than you were before, and your understanding becomes more laborious.

Then you hit a wall.

At this stage, you are no longer able to clearly see your progress. For me, it even regressed to a point where I thought that I knew next to nothing. All of those words I know? Cognates of English ones. The ones that aren’t? Oh, those are just the easy words that I learned a couple of years ago. I imagine that this period is even more difficult if you’re someone who is bad at learning languages, because you’re not sure that you’ll ever get through it. This is where maintaining that same velocity you had early on is vital.

I found that having a personal tutor helps with this. I used Verbling, as it is entirely online and I could work around my schedule and travel. I’ve apparently taken 475 hours of tutoring on there (for a total cost of $10,882). It’s great having a tutor, because you can get feedback that is tailored to you. For example, I have a French vocabulary workbook targeted to C1 learners, and it’s hard to know which of that vocabulary is actually worthwhile and which will get me weird looks. I can run through each with the tutor and ask, “Do people actually say this?”

Beyond that, it’s all about input and production. Listening, reading, writing, talking. It’s especially important at this stage because that new vocabulary will be words and phrases you see very few months instead of every week. Anki helps, but it’s better to see it in situ.

I find listening and writing to be the skills that are the hardest to do as much as I want. This is where you can’t be lazy (and sometimes I am). It’s so much easier to watch a series in your native language, especially if it’s English, than to struggle with your target language. We live in a golden age of language learning resources, but this is one area where things might have actually been better fifty years ago. If you moved to a country that spoke with your target language, you had no choice but to fully immerse yourself, at least in your media. I’ve tried to mimic this a bit in the past by, for example, dedicating an entire year to only watching or listening to things in French.

Now, after ten years of studying French, I’m still studying. Again, I am bad at languages. But, I’ve learned a bit—about French and about learning languages. There’s no substitute for time spent, there’s no magic solution (but there are some good practices)